Inside Story

The storyteller is on a ‘quest for wholeness’ to discover parts of our true nature, something that resonates with him/her. This is the transformational arc: any living thing that isn’t evolving can only be moving towards death. Avoiding the conflict is not only coward, it’s tragic; stories that lack any real reflection of a character’s inner struggle show characters who are “good” because they were born good. This communicates to the audience that virtues like courage, kindness, compassion aren’t choices, but birthrights, and for characters aligned with dark forces there isn’t any hope for redemption.

Writing is a struggle to get to the new place, so it’s a mystery, but the process of unraveling this mystery shouldn’t be a mystery itself, and by following the rules in this book you should be able to go through it.

Characteristics like integrity, compassion, ambition, courage and resiliency manifest themselves when something challenges their existence. This is the inside story, the driving force of the entire drama.

The Beginning

Some stories don’t work, or look flat even if they are compelling, because there is no connection between the external activity and the internal motivations. The internal needs that motivate a character to take action relate to our own inner needs. See for example Apollo 13 (compelling but flat, it talks about a bad day at work: the main character already had in the beginning everything he needed to overcome the obstacles) vs Star Wars (from just a boy, Luke trusts a force greater than himself and becomes a Jedi). Lovell (did you remember his name?) emotionally remains where he was in the beginning; Luke ventures internally to a place where he has never been before; encoded in this simple fantasy is an essential piece of our humanity: exploring the unknown aspects of our human being, towards the connectedness of life. Neither the fate of Apollo 13 or the Death Star is real to us. The life er are concerned about saving is our own. Story is an activator of our internal development as any experience we have in real life. Few of us will ever fly in a spacecraft, but at some point in each of our lives we will be called upon to fight for what is right, to defend our personal boundaries, or to overcome obstacles. How will we approach those obstacles if stories tell us that the road to heroic achievement is reserved only for those who come with their heroic attributes already intact? If we examine the development of our own character, it is the challenges we are forced to face in life that provide the opportunity for self-discovery and personal growth.

The audience enters the story through the protagonist; as the protagonist encounters conflict and obstacles, the audience encounters those same problems. This is how we become engaged in a story. The story becomes more compelling as we watch the characters make emotional decisions that go one way when we know they should go another. If victory goes to the smartest, strongest, and most attractive, in real-life terms most of us would be excluded and therefore there must be something wrong with us if we don’t win. In contrast, look at how audiences respond to a character like Forrest Gump: he is still considered heroic, not because we desire a marginal IQ, but the story reminds us that what we perceive as our own imperfections can be the source of heroism. This way triumph is measured against the struggle within (the only one we care about). The imperfections of characters like Forrest, Schindler, Rocky are real, which informs us that our own inner obstacles are conquerable as well.

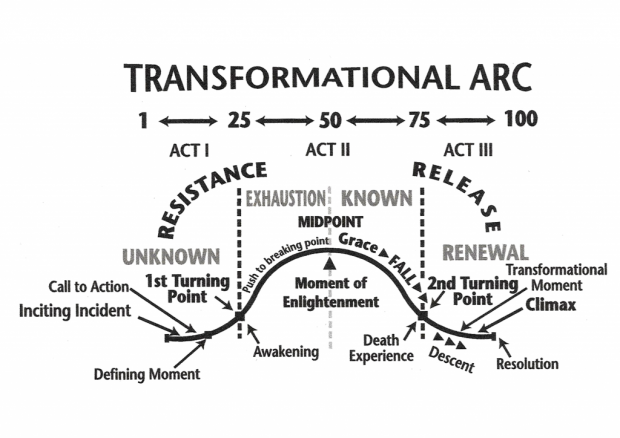

What lies on the surface of a story for a writer is the idea. This is usually a “what if…?” notion that begins to bring a character into contact with an obstacle. The moment that character engages with conflict a natural story structure begins to form around the need to resolve the problem. The three most basic elements of story structure are: Plot (reveals what the problem is and where the action takes place), Character (who is trying to solve the problem), Theme (gives the audience some understanding of why this problem the actions of the character are relevant). The theme tells what the story really wants to communicate. The transformational arc tracks the protagonist’s internal struggle to rise to meet the external challenge by overcoming internal barriers. It reveals how a [character] succeeds/fails to grow and change [arc] withing the context of the conflict [plot] from the writer’s point of view [theme].

Plot

The plot is formed around the motion generated by a conflict, of a great enough size and scope to produce a sense of jeopardy. This automatically establishes a need to get to a resolution, which forms a goal, and the struggle to get to that goal produces dramatic tension which keeps the audience connected to the outcome of a story. Until it’s clear what the problem is, there is no way to care about whether or not the conflict of the plot will be solved – writers should set a strong, clear conflict as soon as possible. The external conflict doesn’t need to be big, but the internal one does. The internal objective creates a supplementary goal that is formed around the subplot, which carries the emotional and thematic content.

Instead of devising a plot that moves the action forward, develop it around the needs of the protagonist to evolve. This begs writers to consider his/her story choices in a very different way and the conflict serves a specific function: to push the inner nature of the protagonist towards maturity.

Remember that completely unrelated conflicts cannot be set into motion and end up at the same climax at the same time. This doesn’t mean that the action can’t move the story in many different directions, or track several different avenues leading towards the single resolution of a conflict, but it mustn’t have two unrelated plotlines, or the audience’s focus will become split, and they will be confused. This is also unsatisfactory and disengaging (see The Fugitive, both protagonists seek justice, it’s a different view on the same theme).

It is essential to name the plotline: name what moves the external line of action forward, using Conflict, Action and Goal. E.g. Schindler defies the Nazis (conflict) and risks everything (action) to save Jewish lives (goal). The writer must have the ability to make conscious, purposeful choices: in the early stages of development, plot details can only be intuited, but at some point it will be necessary to gain a conscious understanding of what the story is really about. Don’t be concerned if the name seems generic: art is in the details and in fact, the more familiar a plotline sounds, the greater the chances the story is striking a strong, universal chord. There’s no such thing as too many stories about greed, love or any other human frailty.

It can sometimes be difficult to distinguish plot from subplot: plot is action (external), subplot is reaction (internal).

Characters

What makes characters tragic is the result of what they fail to do for themselves: the internal goal for a protagonist is always to become heroic. There is always the possibility of failure, or winners would be born, not made.

The audience enters a story through the protagonist – this makes the conflict of the plot personal. Stories that attempt to be told from some neutral perspective will sideline the audience. The protagonist is the character who carries the goal of the plot, and as a strong story has only one plot, it has only one protagonist. If a story has more than one protagonist, each with a separate goal, then it’s imperative to find a creative way to link their goals into one.

Theme

The final scene of Schindler’s List, with the descendants of the survivors placing stones on the grave, is an emotional reminder of how much we all need each other in this world, and how every person can make a difference. We don’t want to be Schindler, but we want to be Schindler-like.

Confusion over the theme won’t engage the audience: Saving Private Ryan ends in a similar way, but the theme goes from “war is horrible” to “war is heroic” to “one’s life value”. Learning to work with the theme is the greatest tool a writer can develop.

Ideas capture the imagination because they mean something to the writer. But if this resolves in just a long speech at the end, it’s probably because the thematic ground didn’t happen to fall into place by itself through the story. This way, the theme is not a tool that can move a mountain. The key to developing a theme is to make it tangible, and to achieve this, it’s given some sort of physical expression: the action of the protagonist.

Theme is based on what a writer believes in. This is the writer’s distinctive point of view, what is personally valued, and through this a writer can come to understand the true intention of his/her story. And this will lead to intentional choices in storytelling.

The point of view encompasses the writer’s vision, passion and values. There are no perfect answers to life’s questions. The writer’s job is to explore these feelings and express them.

This also gives a clue to the design of significant character traits that will evolve logically and non-randomly, from the thematic intention.

Write what you know – but in the realm of the theme, write what you know to be true (a perception is enough, no facts are required). A writer’s view is indisputable. Whether or not anyone else is interested is another subject entirely. Writers must be willing to open their heart and search within to find the connection between themselves and the subject matter. As a theme is a point of view, there are no incorrect point of views. Whether or not that particular vision of life is popular at any given time is not relevant. There will always be detractors from any thematic position a writer holds. Artistically, that’s just a risk that must be taken – otherwise the writing is not honest (e.g. Citizen Kane, it wasn’t a resounding hit in their day, but artists are visionaries and sometimes it takes a while for their views of society to catch up). Other stories can withstand cultural mood swings because there is a layering effect (e.g. Casablanca uses patriotism as the external thematic vehicle that carries the audience deeper into more profound human issues, such as self-acceptance and unconditional love).

Words like patriotism, love, sacrifice carry no implied value (e.g. positive/negative). A personal meaning must be attached to them: there are at least two separate and contrary views about the same subject (we need family and we need our own identity). If these values are held in balance there is no conflict: theme speaks to an aspect of our human reality that is somehow out of balance (family is a solid foundation, but “putting family first” is what destroys Michael in The Godfather). The writer has to look deeper into the source of the imbalance – not to make hateful/racist characters more sympathetic, but to offer some insight into the tragic reality behind their behavior. When we read powerful thematic stories we hardly think of patriotism or heroism; the language of theme confronts us with the reflection of our own heart. None of us invents what it means to be human; we are all the same except in the details.

Thematic goal: narrowing the thematic intention to a singular point of view pulls the story into clearer focus – but this doesn’t mean that a single theme can’t have many secondary ideas related to it. In fact a writer often discovers that what’s on the surface is not what the story is really about. The real conflicts that demand our attention are often buried under superficial distractions. But how does something like this become integrated into a story so that the audience will feel, not just acknowledge, its meaning? Thematic poignancy is established through the audience’s identification with what a character is experiencing and feeling: the theme has to take on qualities that can be expressed physically in both plot and character. The challenge is to give an interpretation that will make it a physical challenge to the protagonist (e.g. Dead Poets Society has “seize the day” and the interpretation is that if the protagonists don’t take control of their life, there are other forces ready to take control of it for them – they have to fight for their own true nature, and thus “to become men, the boys must learn to be true to their nature in order to take control of their own lives”).

Thematic structure: the plot may be the first thing the writer intuitively creates, but it is the needs of the character that must define the journey. Thematic intention defines the internal quest – but theme also helps establish the external issues that will drive the conflict. The greatest of all obstacles is the antagonist, who has an agenda that usually opposes both the internal and the external goals. Utilizing intention enables us to break down the structure of a story in thematic terms: the subject of the theme (e.g. for Dead Poets Society: manhood), point of view (seize the day), context (take control of their lives), struggle (for individual value). Through theme we can form the bone structure of the story: plot/external goal (value the individual – don’t confuse this, the theme of the plot, with the description of the plot explained earlier. The theme represents the personal value that lies inside the conflict) and subplot/internal goal (be true to your nature). And don’t worry if the values sound unoriginal: a strong theme is usually an essential part of our life, which means that we have a great need to hear it expressed over and over. Originality isn’t dependent on what you have to say, but how you say it.

Be especially conscious that you may be dealing with something much more important to you than you realize. Therefore, always approach theme work with immense respect. The value of your thematic message lies in the sincerity and the honesty with which you are willing to expose your own humanity to the world. It involves looking at a reflection of your own life: your choices, your sacrifices, your illusions, and your pain. When it starts to hurt, then you know you’ve hit real thematic pay dirt. In fact, if it doesn’t touch your emotions, you aren’t there yet: it won’t touch the audience either. It takes a lot of processing to identify a theme, and there are no shortcuts: it may take many frustrating days, but it is the most essential work a writer will do. You may process your theme only to realize that there’s more to it than you initially understood – this is how you will remain inspired. You might finding yourself writing of what you don’t know: the conscious impulse that is calling your attention to start the writing process is only the doorway to something deeper inside you that is trying to find expression. If your theme is not chiseled in stone it will have the elasticity to expand and grow: the greatest thing that can happen is for you to experience your own illumination, penciling in thematic ideas to the best of your ability and moving on, trusting that the more you write, the more insight you will gain. Writing is always better when it pushes past what we think and begins to tap into what we feel. Writers who find themselves standing on shifting sands are much more likely to hit something fresh than those only move forward when every step is paved in concrete.

The Fatal Flaw

Is all our pain and sorrow an absurd cosmic joke, or does it have meaning and value? Are the events in our lives ever an indication of absolutely nothing, or is the smallest activity part of a cumulative effect, defining who and what we are? Encoded in our stories is a response to these kind of questions. There are no absolute answers though, so it’s not necessarily the answers we are searching for. Instead, it is the process of the search itself that leads writers to higher ground. This is the sacred trust that is bestowed upon storytellers – to lead humanity to a higher place by illuminating the path ahead and make it a little less treacherous. If we acknowledge that the events in our life do impact us, we connect to everyone else. We confirm that the wide range of human emotions – including negative ones – are not only felt by us, but by all of humanity. We must leave behind any part of ourselves that is obsolete and no longer benefiting our development – this is the drama of our existence.

We see a reflection of our humanity in imperfection – if there’s hope for them, there’s hope for us as well. This is what makes a story compelling: survival on the deepest human level. We all have invested in systems of survival that have gone bankrupt – through relationships, careers, lifestyles and so on. This is the experience of system breakdown, and our stories warn us that the greatest human tragedy is a life that is lived disconnected from its own true nature. It is the quest to know ourselves that forms the grand journey of our lives. When writers touch even a small part of this level of self-reflection, they reach into the soul of everyone.

The young adult is required to cast off ego-driven self-indulgences to become a more selfless participant in the world of career, marriage, and family. But these pieces of our old self are seldom surrendered without a struggle, and this is the nature of the internal conflict that is told and retold in all of our stories: the reclamation of Self. Despair, anger, emptiness are our nursemaids; they care for our souls. We care about the protagonist only if we connect external experiences to internal struggle – and it should be a struggle, or it will remain superficial. How we face our experiences determines who we are, and there is simply no greater purpose for telling our stories.

There are moments in the human drama where the stakes are the highest, where our choices matter the most: what’s going to happen? A need for transformation must be established, and this is where the fatal flaw can be defined. Most of us will fight to sustain destructive relationships, unchallenging jobs, immature behaviour, because it’s easier to cope with what we know than with what we haven’t yet experienced. The fatal flaw is a struggle within a character to maintain a survival system after it has outlived its usefulness. It can relate a physical death, or foreshadow a more metaphorical one, a killing of dreams, desires, passion, identity. It shouldn’t be a judgmental verdict that a writer places on a character, nor should it ever be a moral judgement.

The fatal flaw must be drawn from the theme, it’s the value that opposes the theme and the internal goal (e.g. in Dead Poets Society, the theme is “seize the day” and the internal goal is “be true to your nature”. The fatal flaws therefore must be something that betrays or is false towards the boys’ true nature). This will provoke essential questions: why would someone struggle against being true to their nature? What does it mean? Is it really possible to be false to one’s nature? There are no correct answers, but the technique of finding the fatal flaw demands that writers investigate their own perception of the theme, and it channels the thinking towards issues that will play out the dramatic conflict implicit in the theme.

The fatal flaw should also be used to create a character’s backstory: how did his/her experiences lead to this internal moment of reckoning? By creating a backstory that gives a history to the fatal flaw, a writer is able to connect with the character’s humanity (if someone is difficult and cantankerous, aren’t we giving them more depth if we know it’s because they lost a child?). The protagonist’s behaviour shouldn’t be a random act or simply a dramatic contrivance, but the natural, logical manifestation of a heroic ideal based on a survival system that has outlived its usefulness. It is the tension of hanging on to the old as we are being pulled into the swift current of change that makes our stories alive.

This also defines the context (e.g. in Dead Poets Society, context is harsh and unaccepting; judgmental and disrespectful).

Case study from Lethal Weapon:

- Subject: Life and death

- Thematic point of view: Choose life

- Plot (external goal): Value life

- Obstacle: Devalue life

- Context: murder, corruption

- Subplot (internal goal): To connect with others

- Fatal flaw: Disconnected from others

- Character traits: detached, reckless, suicidal

Inside Structure

Architects don’t dump a pile of wood on the ground and call it a house. As the process of writing ceases to be a mystery, you can look past the boundaries it creates and find opportunities for unique self-expression.

The harder an issue is to solve, the greater the conflict. But resistance can’t intensify indefinitely: the tension will reach a breaking point and release will follow. Holding this pattern of resistance and release in some sort of balance (almost 50/50) will help establish and maintain a stronger dramatic tension.

What was unconscious in the beginning becomes conscious in the end. From this perspective, stories such as Schindler’s List aren’t about opportunistic men caught in the crossfire of history who must make selfless choices to help others survive, but stories about people (just like us) caught between the desire to stand alone and the need to be connected to others. The dynamic tension between this type of conscious and unconscious split is part of all of our lives, and it constantly demands that we make choices. There is no right answer, where there is tension there is an imbalance in the force between the opposing energies.

ABC: There are three primary plotlines in a story: a plot and two subplots.

The plot is the A story, that can only be solved if B and C are solved.

External action causes internal reaction, which leads to external response and internal shift, which resolve the external conflict. When the Inner Conflict rises to a level that is great enough to demand Resolution, it establishes a Goal that inspires Action – this forms a structure which is the nature of a subplot (sub with the meaning of “foundational”, it gives meaning and value to the action of the plot), or B story (fatal flaw / internal conflict). It reveals what the protagonist needs to achieve internally to resolve the external goal of the plot.

The A story is dependent upon the B story for resolution. As a writer, rely upon what you experience in your own life to answer how the inner conflict is resolved. Can inner transformation ever be a passive act? There must be actions that will validate whether or not that change has occurred. The internal change is demonstrated in relationship to something in the outer world. A husband’s infidelity can’t be fixed by an apology and a claim that he’ll never do it again – only time and consistency in relationship to his spouse will demonstrate that. The relationship conflict form the second subplot, called C story.

There can be some confusion, but there are distinctions: in the A story, a relationship conflict is driven by external obstacles that block people from achieving the external goal; in the C story, a relationship conflict primary focuses on the protagonist’s internal conflict and it serves to internally challenge him/her to change and grow in relationship to someone or something.

To recap:

- External events in the A story represent the opportunity in the outer world for the protagonist to grow and evolve towards the thematic value. How we rise to a challenge by making choices and accepting change

- The internal conflict (fatal flaw) in the B story represents what is lacking inside that is forcing the protagonist to grow towards the thematic value. How we are capable of self-destruction and re-creation

- The relationship conflict of the C story shows the impact that the lack of this value is having on the protagonist’s ability to connect with someone/something. How we relate to each other

Example from Casablanca: In A, Rick is asked to save Laszlo from the Nazis. In B, the theme is expressed by showing that Rick believes he needs nothing and no one, and his manner is brusque (Rick will need to connect with others). In C, Rick’s lack of valuing others leaves him isolated (Rick learns to love unconditionally through his reunion with Ilsa).

As a writer you should ask yourself: in order to resolve the external conflict, what will the protagonist achieve internally at the end of the story that he/she is not capable of achieving at the beginning? In an early draft a writer may be inspired by complex plot contrivances that produce surprising twists and intriguing dilemmas, but as the writing process evolves, it is essential that you develop the theme in the form of emotions such as pain, emptiness, desire, and need.

Case study with Lethal Weapon. A (plot): Riggs and Murtaugh must stop the dangerous drug cartel. B (internal subplot): R&M learn to trust life. C (relationship subplot): R&M must connect and form a team.

Unknown-Exhaustion-Known-Renewal forms the three-act structure (the second act is divided in two halves), and act breaks and page counts can give the writer guideposts within which to organize and make maximum use of structural elements.

Act I

The story must begin where achieving the value and purpose are necessary and relevant. The exclusive purpose of the first act is to set conflict into motion – everything must serve the function of establishing the conflict. It isn’t necessary to know the end of the story before beginning to write, but only to know the point of view the ending will express. The end itself is just a matter of creative choice.

The first act will show hoe and why A, B, and C storylines are interrelated. Example: if the A story revolves around a cop solving a murder, then the audience needs to learn about the murder in the setup, and they must be aware of any external obstacles. To set up the B story, the audience needs to be shown the internal issues creating obstacles to solving the murder as well – for instance, the cop might arrive at the crime scene hungover. If this stands alone, the protagonist will merely come across as a worthless drunk – it’s important to show a relationship conflict (C story) between this behaviour and what is causing him to drink excessively, or the audience won’t care. His wife can just have left him.

There are then four possible scenarios for the outcome, and it’s vital to point the story in one of these directions in the setup, so that the audience has some sense of where the story is taking them:

- The cop catches the killer (A) because he is able to stop drinking (B) by resolving the issues that caused the relationship conflict (C): heroic arc of character, once we deal with our inner demons, we are capable of dealing with the demons in the external world

- The cop doesn’t catch the killer because he is unable to stop drinking as he was unable to resolve the relationship conflict: tragic, if our internal demons aren’t dealt with, the external demons will prevail

- The cop catches the killer even though he fails to stop drinking as he failed at resolving the relationship conflict: tragic, the cop achieved a hollow victory; he looks heroic on the outside, but on the inside he is at risk of becoming a demon himslef

- The cop doesn’t catch the killer even though he does stop drinking through resolving the relationship conflict: this scenario can be heroic if it shows us that catching the killer wasn’t really the right thing for him to do (e.g. the killer was a victim) or cynical if the message is that no matter how much we try in life, we ultimately have no control over the actions of others and over outside circumstances (careful though, the story itself might come across as pointless)

Notice that in all of these scenarios, the C and B stories are connected.

If the three plotlines are well established, the first act will be strong. However, conflict that is strong doesn’t necessarily imply that the actual writing is powerful and compelling. This quality will depend on the writer’s ability to communicate the layers of internal and external conflict with subtlety, subtext, wit, nuance and insight. There are no simple rules to tap into these qualities, but there is one very powerful source of inspiration to avoid mediocre, predictable storytelling: follow the image. What you want to transmit when action, dialogue and setting work in collaboration to imply an image. You are constructing something that mirrors or symbolizes its value. For example, in the opening scene of Rocky, as we become engaged in the fight between Rocky and his opponent, the imagery (desolate reality, human waste, disappointment = dark, shabby atmosphere of the fight arena) makes us feel that the stakes are very, very high, because the images that envelop the fight convey a foreboding sense of doom. In the first act less emphasis is paid to the big prize fight to defeat the world champion than to what Rocky is actually fighting for. Include your knowledge of the theme and how it translates to the fatal flaw of the character. If the readers identify themselves with the protagonist’s difficulties, they will be emotionally engaged when in the second and third act you will focus on the external conflict. Working with image demands that you ask yourself: what does this mean to me? What am I really trying to say? An image is not a direct replication of a situation, but a personal interpretation of what that situation means, so it is essential to have a personal perspective or bias.

Inciting Incident, Call to Action, Defining Moment: if the audience doesn’t understand what’s at stake they won’t be concerned about what’s coming next. Many writers tend to confuse subtlety with ambiguity: it may feel appropriate to draw the audience into the mystery of the situation by leaving the setup vague and non-specific. This doesn’t work!! Until the audience knows what’s going on in a story, they won’t care about the outcome. Utilize the first pages of your book to clearly set up the conflict in all three storylines. Two common terms used to identify how the A story is set up are the inciting incident (it doesn’t have to directly relate to the protagonist, it simply instigates the beginning of a chain of events that must eventually pull the protagonist into the story and call him to action) and the call to action (it is absolutely mandatory. Willingly or unwillingly, consciously or unconsciously, in the first act the audience must be able to clearly track the protagonist’s actions as he is being pulled into the central conflict of the story).

Example: Star Wars, not only is Luke Skywalker unaware of Princess Leia being captured, he doesn’t even know who she is or that he is part of a legacy of Jedi knights. It takes nearly fifteen more minutes before Luke’s destiny becomes directly intertwined with the princess’s and he is called to rescue her.

Notice that the setup of the A story is clear (through inciting incident and call to action) and the audience understands the external conflict. Setting up the B and C storylines can be a little more complex in terms of making the conflict clear so that the audience will become emotionally engaged. This needs a defining moment that brings clarity and focus to the internal dilemma of the protagonist: it clarifies the nature of the conflict and what it will take to resolve the crisis. In the beginning it’s fine to use some amount of subtlety, but don’t go too far without making sure that the internal conflict gets clearly spelled out, or the audience may not fully understand what is really at stake. Use finesse and sensitivity though.

In Rocky, the coach calls Rocky a “tomata”: he isn’t interested in working with a fighter who doesn’t have any real fight left in him – if Rocky doesn’t learn to stand up and fight for himself, he’s going down for the count. In American Beauty the writer is even more direct: the protagonist says “In less than a year, I’ll be dead. In a way, I’m dead already [shower, naked body is silhouetted, it becomes apparent he is masturbating]. Look at me, jerking off in the shower. This will be the high point of my day. It’s all downhill from here” – and we then see he’s right. Anybody. and Lester himself, ceased to care about him. In Dead Poets Society John Keating cautions his students to seize the day and make their lives extraordinary.

All of the plot elements of the first act have something to do with what the protagonist doesn’t know. He doesn’t know how to resolve the conflict. It’s important to identify the system of resistance that is keeping the protagonist from getting to the goal of resolving the conflict. It is important ti set your character up in some condition of unknowing in Act I – this can include unawareness, ignorance, and so on. Transformational change is the act of growing into new consciousness.

First Turning Point: a turning point is an escalation of the conflict that turns the story in a new and unexpected direction, substantially raising the stakes for the protagonist. Something big and unforeseen must happen to change the course of action the protagonist is taking. In the A story, the first turning point occurs as a result of a shift in the external action. Look at your theme to define the obstacles that appear in the protagonist’s path. The theme of Rocky is the heroic path to redemption: he has given up on himself; the turning point happens when Creed chooses Rocky as his opponent for the World Heavyweight title: he is given a chance to redeem himself, albeit one so huge it clearly dwarfs him. In The Fugitive, Dr. Kimble has been falsely accused of murdering his wife (A story); he is forced to board a bus that will take him to a death row prison cell. Along the way, another prisoner attempts an escape that causes the bus to crash on a railroad track where a train is coming; Kimble is able to evade the clash, becoming a wanted fugitive. This point is strengthened when a U.S. Marshal vows to relentlessly hunt him down (A story), but Kimble also makes a critical decision that will greatly influence his fate: at the moment of impact, he decides to risk his own life to get an injured guard to safety. While this leaves the guard alive to become a potential eyewitness, the writer shows the audience that Kimble is not a man who will sacrifice others to save himself; we’re not just cheering to save an innocent man, we’re cheering for a man who is worth saving. Because he has proven himself worthy, a firm hand helps pull him to safety from the inferno around him. One of the other escaping convicts tells him that he doesn’t want Kimble to follow him: this sets the tone for the entire second act. If Kimble is to make his way back to the world, he must find his own path (abandoning the false security of his old identity; no longer the proud doctor, but a common man being forced to take on life in a new way).

Awakening: at this point it’s necessary to look into the impact the external experiences are having on the internal reality of the protagonist. Because the purpose of a story is to move a protagonist towards resolving conflicts, the writer must design the plotlines so that the protagonist is constantly confronted with a greater and greater need or urgency to achieve those goals. Hence, the situation must constantly worsen or heighten. This will shake, if not completely unsettle, the foundation of the protagonist’s inner world. If a strong fatal flaw has been established in the setup, then the inner world will be in grave need of a shakeup anyway. Remember, the fatal flaw feels like a condition of being stuck or trapped (Luke Skywalker feels trapped in adolescence), and the awakening is a wake-up call for the protagonist, though generally not a welcome one (Luke wants to grow up, but the reality that there is evil in the world is not what he expects or wants, especially when that evil kills his family and threatens the future of the Republic; Harry and Sally want love, but not the pain and heartache that are part of the bargain). Its function is to set the story on a new course that will disrupt the status quo and add more urgency to the need for resolution, especially when set off by a strong internal conflict. Use every means possible to call attention to what is happening: if a turning point does not increase the audience’s emotional involvement, it will be very difficult to sustain their interest.

Act II – Part One

The first half of the second act is where old values and distorted perceptions are challenged. Anything that doesn’t serve either the external or internal needs of the protagonist may be broken apart: we have to exhaust everything we know, or think we know, in order to get to someplace new. It is likely that the protagonist’s actions are not leading towards a resolution of the conflict, especially internally, because he is stuck making decisions that feel safe and easy, and we in the audience will usually root for him – but there is something in the back our mind that just doesn’t feel right.

A, B and C must keep traveling in threes. It’s important to keep pushing the protagonist toward exhaustion in all three storylines:

- Attempts to solve the external problem A will be ill conceived, thwarted, misjudged and so on. This will lead to frustration, false hope, disappointment, and even chaos

- In the internal conflict B, denial tends to reign supreme. The awakening may have brought about the dawning of new consciousness, but it’s still early and the protagonist doesn’t know what’s really going on

- This denial especially impacts the relationship subplot C, because the protagonist lacks understanding and the ability to connect to real inner emotions, which makes relating to what he wants and needs nearly impossible – so not relationships in general, only with regards to the goal of the plotline (if Harry and Sally need to fall in love, at this point they become friends rather than lovers, or can’t stand each other). Their actions must tell us that they are in resistance to the truth (in a story about a woman married to an abusive man, during the first part of the second act she will be doing everything she can to produce harmony), so we sense a discomfort and tension

Midpoint: as things continue to worsen and become more frustrating, the ego strength of the protagonist will begin to break down. This is part of the essential function of exhaustion: where there is a breakdown, there is potential for something new. The midpoint creates a breaking point in the dramatic tension. Despite willful attempts to make things turn out the way the protagonist wants, something happens, usually in the A story, that rips the sense of control from his or her clutches. The more forceful this incident, the more powerfully your protagonist will react (see The Fugitive, Kimble can run no more and is cornered by his pursuer, who doesn’t care whether Kimble is guilty or not. Kimble realizes his options are exhausted – but then he realizes he still has one more option he never considered, and dives into the unknown waters below. In the first act Kimble is presented as a victim – Gerard is the voice of justice, how can he be indifferent to a man’s guilt or innocence? This is the thematic question of the story. Perhaps the thematic insight is that trye justice in life answers to a higher source than our human sense of correctness; difficult, unfair things happen to everything in nature, the real question is: what am I going to do about it? Only one course offers hope, and Kimble’s courage is rewarded with guidance: no longer the victim, Kimble now intends to catch the man himself). The nature of the transformational arc is that it will rise or escalate as the tension to resolve the conflict intensifies; but no conflict can go on forever unabated, so after the breaking point a shift occurs that allows something new to enter the picture, usually in the form of new information or a new perspective: this is the moment of enlightenment because it casts a new light on the problem and allows the protagonist to begin to see how the conflict might be resolved. The conflict is shifted out of resistance and released in the direction of resolution.

Even though something happens in the A story, it is not the physical action but the internal reaction to the midpoint that opens up the new idea that allows the protagonist to move forward towards resolving the conflict. This enlightenment also comes about because the protagonist has begun to see how his own behaviour (fatal flaw) impacts resolving the conflict. Since the fatal flaw comes directly out of the writer’s thematic point of view, it is that thematic content that is specifically expressed at the midpoint. This is the truth that the protagonist begins to understand.

The midpoint not only reveals the truth to the protagonist, but it also reveals the writer’s truths to the audience. Through the protagonist’s actions and reactions, the writer’s thematic values are clarified and defended at the midpoint. This is the place where you can usually get away with demonstrating a principle regarding the thematic value, even through a speech. The midpoint happens for A, B and C – though it’s not essential that they all occur at the same time and in the same scene – the order also doesn’t matter.

You can also look to the midpoint to understand your theme. What is physically shifting the action toward resolution? What is internally motivating the protagonist to take the new course? If nothing is motivating the protagonist, your theme might be underdeveloped. This is also a good place to see if the theme you think you are developing is the same theme the story actually wants to communicate. Writers are called to write what they don’t know, therefore open yourself to the possibility that the “new thing” may be breaking into consciousness for you as well as for the characters in your story. You can pay special attention to the midpoint of a story to find clues about what the writer’s conscious and unconscious intentions might be. It is also a very good place for both the protagonist and the audience to rest and be reminded of the value and importance of the quest itself. You can use it to re-write the first half of the book if it didn’t use the theme, for example an undeveloped fatal flaw.

In Lethal Weapon, Riggs saves Murtaugh’s life, and this brings the two closer to start working as a team (relationship C moving towards the midpoint); Riggs begins to laugh and relax which is an indication that the internal arc of character B is also moving towards the midpoint where he will find purpose in his life again; and the truth of what is really going on in the plot A takes shape for the protagonists and the audience when they know who they are fighting and why.

Act II – Part Two

Period of Grace: a great amount of energy has been used, and now we are at the summit and we have the chance to rest and renew our energy. The protagonist will be inspired and motivated to face what lies ahead with renewed vigor and resolve. It can be a few pages long, or as short as a single scene. The audience will welcome this rest – very often they will hope that the story will end here, but then we are also aware there is too much still unresolved. The grace period can even give the false impression that all is well and the conflict is abated. Many writers take full advantage of this misimpression and intentionally lure both the audience and the protagonist into a false sense of safety. The protagonist can lower defenses and even become too sure of himself. The grace period should show us the protagonist’s potential of whether she can achieve the internal and external goals. In the external plotline, this is where the weakness in an opponent’s strategy is exposed. But more importantly, you want to explore what is shifting inside the protagonist that will lead her to transformational change. But it must also be evident that there is work still to be done because change cannot be achieved without commitment, hard work and letting go. It’s a gift/reward for having struggled to achieve greater self-awareness, and it increases access to the realm of consciousness, and what was unknown externally and internally becomes known.

Fall: Higher consciousness alone is not enough; it must be acted upon before it can be transformed into something greater within us, and this is the nature of the challenge that still lies ahead. In storytelling, the principle must be evident or the arc of transformation will feel false. The internal storyline is not complete. There are still unresolved complications that will cause a great undoing, a fall that sets relationships, ambitions, aspirations and achievements into a decline. Lies and half-truths are about to take their toll. Miscommunication and misjudgments occur, leading to bad timing and bad planning. The result is often a sense of betrayal. Often the biggest reason for the fall is that, despite the enlightenment, the ego won’t easily let go of old perceptions and values. There is a conflict between old and new self that is struggling to emerge, and protagonists can become ambivalent, indecisive, and even disengaged from the goal: they are often directly or indirectly responsible for the fall itself. Sometimes, the fall happens if the new consciousness is more than he can handle. In Dead Poets Society, the new personal freedom leads to irresponsible behaviour, and one the boys foolishly mocks the headmaster.

Death Experience: life will often get a lot more difficult before it gets better. Transformational change is the death of an old system of survival (the fatal flaw) and the birth of a new one, let go of what is obsolete and surrender to the new. The writer forces the protagonist into a situation that will about her undoing, which is how we arrive at the second turning point: a very big obstruction into the wheel of progress for the protagonist. What’s the worst thing that can happen, related directly to the internal struggle of the protagonist? Using the internal struggle has a bigger impact, the protagonist feels to have lost everything, especially the gifts received during the midpoint (in When Harry Met Sally, the theme has to do with how essential it is for lovers to be friends, therefore the worst that can happen is the loss of their friendship). Consider your own emotional response to the experience of loss: unbearable sense of disillusionment, anger, betrayal, failure, sorrow, defeat. We’ve done the internal work and it seems like a cruel trick of fate that our lives aren’t working out the way they’re supposed to. The one thing that can never be taken away though is the enlightenment of the midpoint. However it can be unwanted and despised because it is now attached to the loss, which causes profound internal crisis. It feels like all the internal development is now lost, but this isn’t the end of the story – if the protagonist is willing to fight. This is the challenge of the third act.

Tragic characters miss the opportunity to reach new knowledge.

Remember not to stay in your comfort zone when exploring the theme in the second act: explore the shadows, as the core is often there.

Act III

Often, when terrible things happen to the protagonist, a writer’s instinct is to jump in and rescue their main character as quickly as possible. Don’t do that! There should be a downward slide well in progress since the midpoint; the conflict has picked up a lot of momentum: the more unstoppable it feels, the more urgency the audience will feel as well. The third act is leading towards a climax, and this is not the time for things to slow down. Everything is at stake, don’t resolve anything. This mistake is especially common in the relationship subplot. This is where the protagonist will feel the most disillusioned, cynical, angry, betrayed and vulnerable; these emotions are what will make your characters most human – most like you and me. The descent is a time of pain that reveals the protagonist what life will be like if he refuses to change and grow. This is also a time when the protagonist will feel most acutely alone, even if someone is with him, because transformation is a personal choice and the help of others doesn’t work. Then we surrender our ego system and we are forced to engage in a new way. Transformation demands sacrifice. The death experience pushes us beyond what we thought we could endure. The protagonist must feel the depth of the emotional loss suffered at the second turning point. If he doesn’t experience such feelings, then the turning point isn’t strong enough and the loss isn’t great enough. If this part of the story is weak, it is important to look within yourself; you can’t write the protagonist’s pain if you don’t honestly feel it. This doesn’t mean that you have to understand it; sometimes our pain runs so deep that the only part of it we can touch is the sense of fear and confusion surrounding it. But if you are at least honest enough to show us the fear and confusion, we will still be able to connect with the story’s emotional reality.

The goal of the plot itself must be falling apart as well. The ending of a story takes a heroic turn when the protagonist is able to pull herself out of the descent by making choices and taking actions that not only resolve the external conflict but also revitalize her inner sense of purpose and value.

Transformational moment: The decision by the protagonist is the pivotal event of the entire story. The protagonist decides her own fate. Afterwards, in the climax, the protagonist will take physical action towards resolving the conflict and achieving the goal of the plot, but it is this internal moment of decision that marks the true transformation of character. Often the TM is the climax of the B story. Transformation is always a conscious choice. The protagonist makes the decision to do what must be done to resolve the external conflict, thanks to her highest point of consciousness.

Climax: the climax brings the conflict to a conclusion. To resolve the dramatic tension, the thing that stands in the way must be beaten, outsmarted, overcome, killed, destroyed, won over. The antagonist is the physical representation of the interior conflict. Don’t link the climax with something disconnected from the theme, or the audience will be confused (see Million Dollar Baby, where euthanasia just happens to be part of the outcome of the story, but it looks like it brings up the issue of the right to die. Up until the death experience, it was a story about the courage it takes to become a winner. Maggie could have take the decision to end her life in the beginning, so this has become Frankie’s story and “loving someone enough to let them go” – a strong statement, but it has nothing to do with the theme). Finding a whole new thematic direction at the end of a story is not unusual or counterproductive – it may be a strong indicator that the writing experience is alive. But the new thematic direction must not remain unprocessed: the new pathway must be integrated into the rest of the story. The question is: has the protagonist achieved something in the end that he was not capable of achieving in the beginning?

Resolution: it is the start of something new, it gives the audience a glimpse of what the new encounter with life will look like. It has a great symbolic value: there is always more life on the other side of our troubles, and the hardships and suffering we endure are worth the effort. There will be more struggles on the horizon, but the protagonist is now better equipped to handle life’s battles. Some stories utilize irony and paradox to leave the audience stimulated and questioning their own values and perceptions (see the end of American Beauty where Lester addresses the audience about the beauty of life despite the fact he is dying). What was unbalanced regain balance, but the questions remain. “Self vs others” is a great theme, and there is no correct answer (Dead Poets Society: it doesn’t create a new imbalance towards Self; it says that even with the boundaries of society, the boys can maintain their own integrity. Good tragic endings like The Godfather III doesn’t leave us feeling as hopeless and miserable as the protagonist). Before this point a pause was needed, but the intensity must be kept strong here and push the protagonists beyond their limit. You don’t want the audience to remain passive, but to emotionally engage them.

Epilogue: it’s not just that we identify with protagonists – it’s that they were already part of us. They gave our emotions an identity, and they showed us how to process them – especially the painful and difficult ones – so that we can continue to evolve, moving ever after into a larger world of infinite possibilities. As a writer, what good is the gift of a great story if it is never opened and shared? And would the world be better off without the contents of what lies within, no matter how terrible? Dare to be guided by your passion, open your gift and release into the world of infinite possibilities the truths that reside there.